hacking narratives

Meet the stories of social innovators who are transforming the way we talk about migration.

If we understand migrants as agents of change who seek an opportunity to improve their reality and that of many people, we can hack the narrative. For this reason, we gathered four stories of migrants who transformed their reality through social innovation initiatives.

Manu Mireles

Manu grew up in Venezuela, but found himself in Argentina. In her new country, she founded the Mocha Celis Civil Association, which provides educational and professional training to trans, transvestite and non-binary people. “It is a space that embraces, contains and accompanies,” he says.

Manu’s origins shed light on the person he would become: his grandmother was a peasant woman who learned to read on the sly and, as soon as she could, migrated from the countryside to the city.

Once in Caracas, Manu’s family lived in a neighborhood of high vulnerability and poverty, so every Christmas his mother was in charge of collecting toys so that no child in the neighborhood would lack a gift.

Both women were a great inspiration to Manu when it came to facing adversity and caring for the community they lived in. Manu, who holds a BA and MA in Education, and a PhD in Public Policy, puts much of her experience and knowledge into practice through non-binary trans activism.

Mocha Celis has employability programs, a popular gender school and an area of access to rights, among other innovative projects. In addition, they have published a documentary, two books, comics and reports. free access on its website.

![]() Get to know the full story of Manu Mireles in the podcast

Get to know the full story of Manu Mireles in the podcast

Hacking Narratives.

Laura Herrera

Laura Herrera, a social communicator, arrived in Argentina from Colombia at the age of 29. Her desire to work in the most vulnerable areas led her to join the Jesuit Migrant Service (JMS), first in her native country and then in her country of arrival.

During his university years, he became involved in communication for social development, and dedicated himself to doing his practical work in highly vulnerable areas. She then came to SJM and pursued a graduate degree in education and politics, motivated by working with children and youth.

In her new country, she discovered all that Colombia represented in her identity, which made it easier and more special for her to work with families that migrated from her own country, sometimes because of the armed conflict.

Through the Soy Refugio initiative, Laura worked with women from many parts of the world, seeking to create “something collective, in terms of local integration and income generation”.

The migrant women make tote bags, mugs, diaries and other products that they market with the guarantee that a migrant woman was involved in their production in search of social and economic integration and independence.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Hacking Narratives.

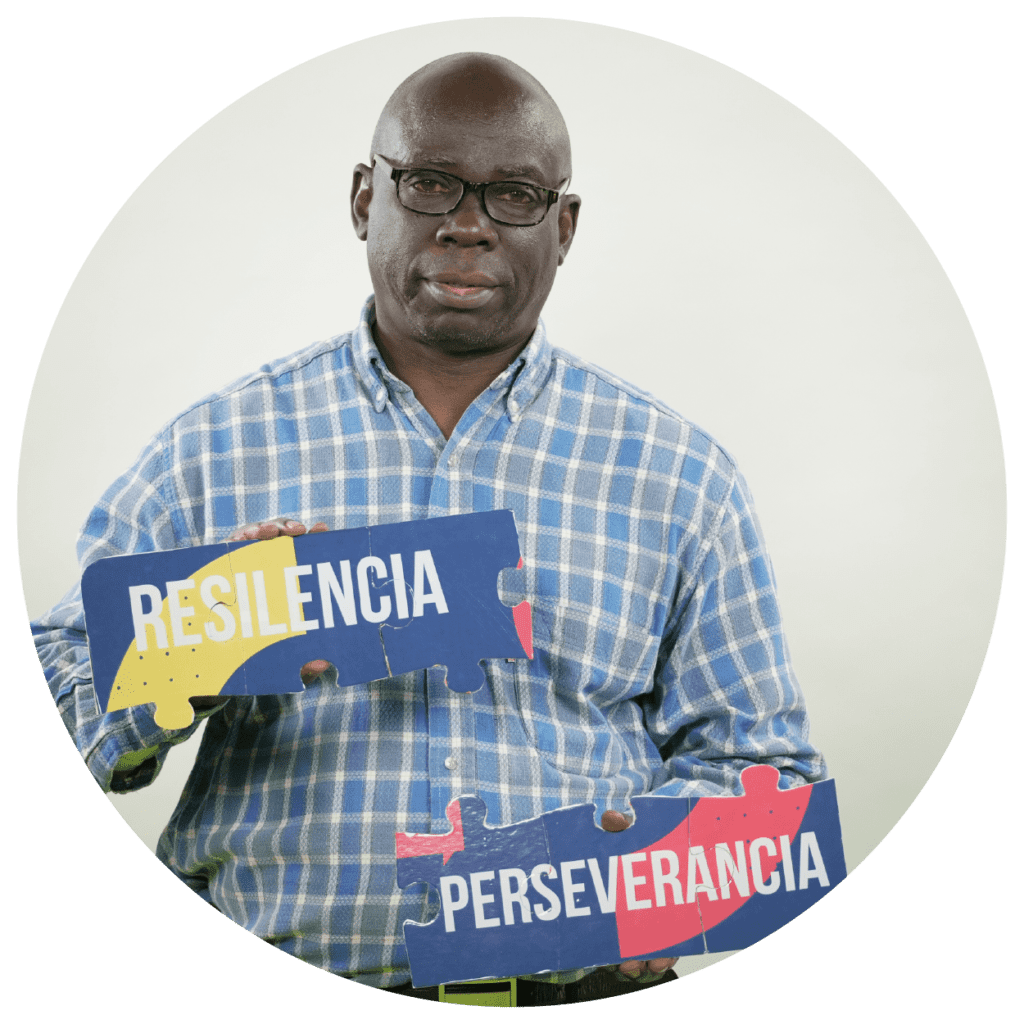

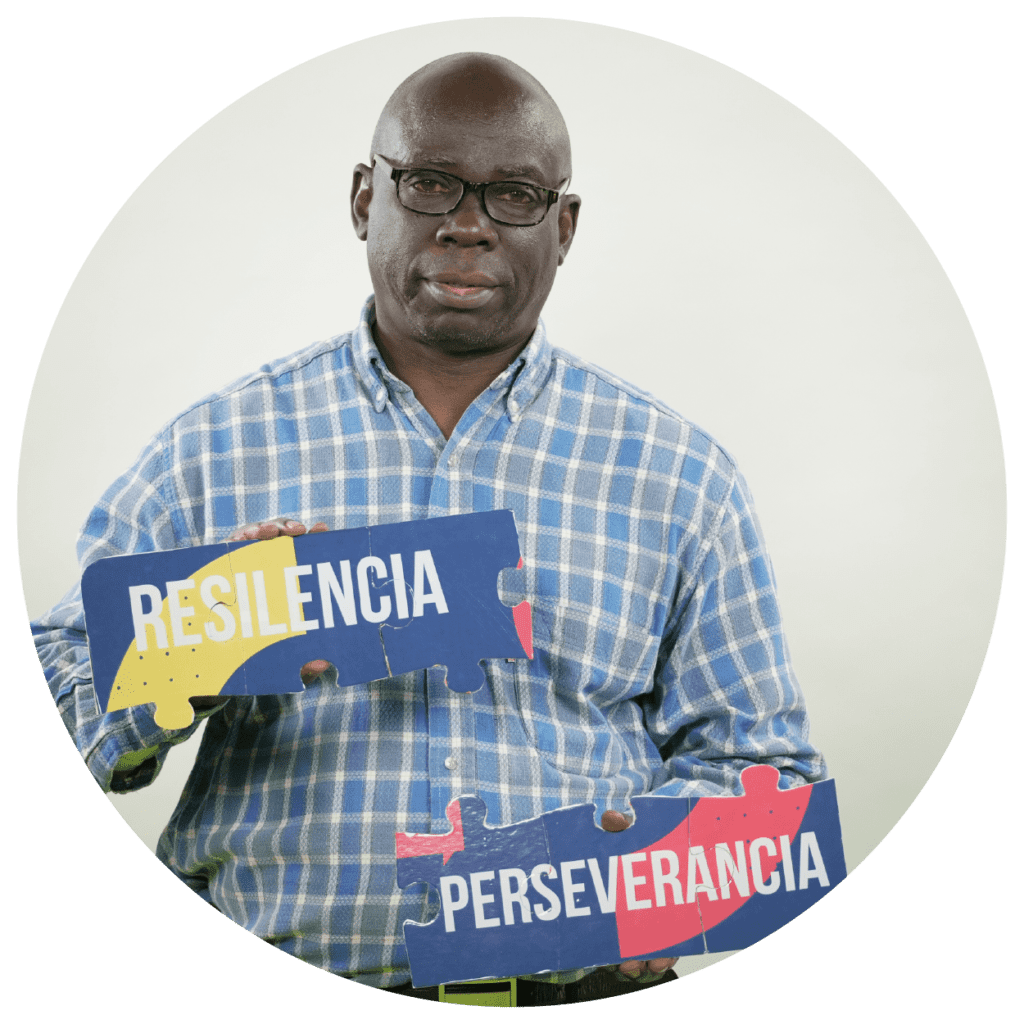

Nengumbi Sukama

As for many of his fellow Congolese, for Nengumbi Sukama, migration was a matter of survival. The military dictatorship of Joseph-Désiré Mobutu exercised a great political persecution that affected Nengumbi’s family, as his father was an opposition politician.

Nengumbi studied economics at university, where professors showed how the dictator Mobutu was ruining the country and encouraged students to protest. Nengumbi, coming from a political family, quickly rose to become a leader and political activist in Human Rights.

His father, aware that his family was in danger and that his son had already been arrested three times, advised him to leave the country. “The old man said ‘I don’t want to lose you’ so you have to go.” Thus, Nengumbi arrived in Argentina in 1995.

A year later, he founded the Refugee Forum in Argentina to act as an interlocutor between refugees and asylum seekers with UNHCR and the Argentine authorities. Then, in 2002, from England, he founded the Defender of Minority Victims of Racism in Argentina, IARPIDI.

With these initiatives, Nengumbi and his colleagues achieved something very important: the recognition at government level that there is structural racism in Argentina.

“It is still said to this day: ‘in Argentina there was never an Afro’, which are historical falsehoods,” says Nengumbi. “But today, as a result of the work we did, we generated a change in the perception and in the way of speaking of a sector of the Argentine political class and leaders, especially in human rights associations.”

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Hacking Narratives.

Julieta Casó

Despite being born in Venezuela, Julieta Casó, sociologist and social psychologist, has always felt like a migrant because her parents are Argentinean.

Since she had family there, Julieta left with her two children thinking that she was returning to her origins rather than migrating. He thought he had a family, that he would not miss Venezuela so much and that it would not be so hard to find a job. But the opposite happened.

In spite of experiencing great difficulties, Julieta made an effort to get a job in what she studied, and wanted to help Venezuelans who were going through the same thing with her experience. This is why he created the Guáramo initiative, to “stay in touch with my profession and contribute something to Venezuela”. Liliana Miñán, a graduate in Social Work who was born in Argentina, migrated to Venezuela and returned to her native country 20 years later, joined the project.

Thus, since its inception Guáramo has been formed by people from both countries. The project joined forces with Alianza por Venezuela’s employment exchange to analyze the labor migrant profile, in an initiative called “Empléate con Guáramo” (Get Employed with Guáramo).

The purpose of this and other innovations is to change the migrant labor culture that applies for lower paying jobs and working conditions, being overqualified for them. “Work is not only to earn money, it is indispensable because we have to support ourselves, but work is a form of personal development,” says Casó.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Hacking Narratives.